|

|

- Search

| Arch Aesthetic Plast Surg > Volume 30(1); 2024 > Article |

|

Abstract

Copolyamide fillers, such as Aquafilling, have been used off-label for breast augmentation in many countries, including Korea. However, safety concerns have arisen due to reported complications, including induration, masses, mastalgia, firmness, asymmetry, migration, infection, and dimpling. We report the case of a 33-year-old woman who presented with distant migration of copolyamide breast filler to the left lower abdomen and inguinal area following mammography for breast cancer screening. This case highlights the potential risks associated with the migration of copolyamide breast fillers, particularly in the context of cancer screening procedures, and emphasizes the importance of awareness and vigilance among clinicians and patients.

Aquafilling (Biomedica, spol, s r.o.), also known as Los Deline and Activegel, is an injectable hydrophilic gel composed of 98% sodium chloride solution (0.9%) and 2% copolyimide [1,2]. First introduced to the market as a facial filler in the Czech Republic in 2005, it has since been used off-label for breast augmentation in many countries, including Korea [3].

However, safety concerns have arisen due to reported complications associated with copolyamide fillers, including induration, masses, mastalgia (breast pain), firmness, asymmetry, migration, infection, and dimpling, which are attributed to the copolyamide component [4-8]. Consequently, the Korean Academic Association of Aesthetic and Reconstructive Breast Surgery has recommended against the use of copolyamide fillers for breast augmentation until their long-term safety can be established [2]. Although local migration of copolyamide fillers is relatively common [7], the current literature includes no reports of distant migration following mammography.

This case report details the rare case of a 33-year-old woman who developed copolyamide breast filler migration to the lower abdomen after undergoing mammography.

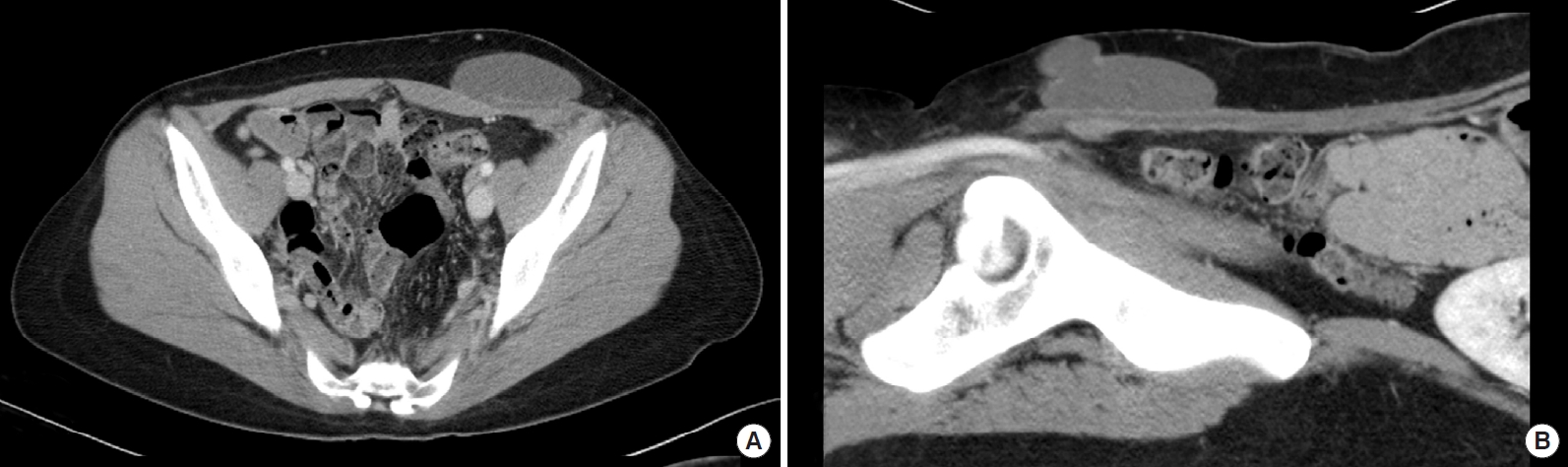

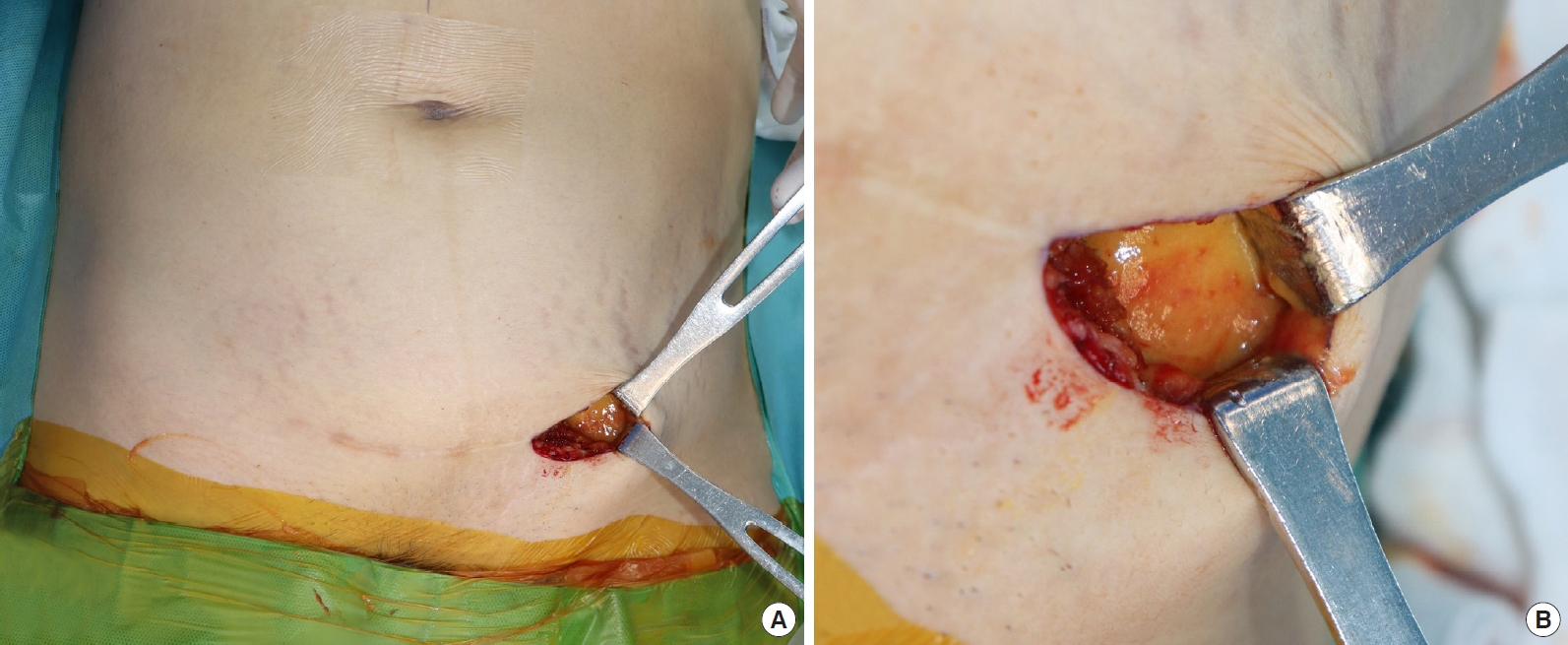

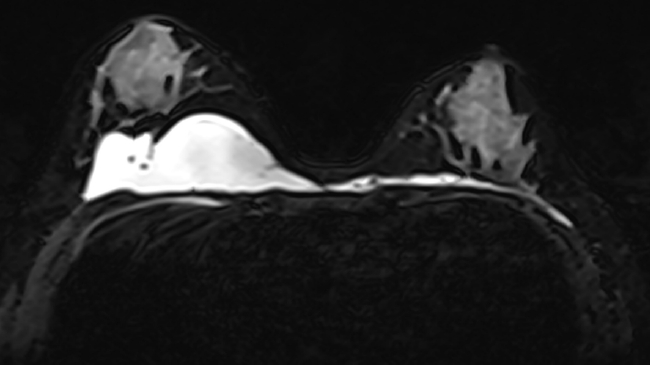

A 33-year-old woman with a history of cesarean section 1 year prior, as well as bilateral breast augmentation using Aquafilling filler 9 years earlier, visited our clinic. The patient presented with decreased size of the left breast and a palpable lump in the lower abdomen, which had appeared following mammography for breast cancer screening. On physical examination, we observed asymmetrical breast volumes but detected no nodules, induration, dimpling, or signs of infection in either breast or in the lower abdomen (Figs. 1, 2). Breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed foreign body injection in both the retroglandular and subpectoral spaces, with no abnormal enhancing lesions in either breast (Fig. 3). Additionally, abdominopelvic computed tomography confirmed the migration of a foreign body to the lower abdomen and left inguinal area (Fig. 4).

After confirming the absence of nodules, fibrosis, or infection, and noting that the Aquafilling material was well-localized within the breast on MRI, we opted to remove it using liposuction for the breast and direct excision for the abdomen.

Under general anesthesia, we utilized ultrasonography-guided liposuction to remove the foreign body through a 1-cm incision in the lateral inframammary fold of each breast. To address the distant migration to the left lower abdomen and inguinal area, we extracted the foreign body using direct visualization through the existing Pfannenstiel incision (Fig. 5). The patientŌĆÖs postoperative course was uneventful, with no complications in the breasts, left lower abdomen, or inguinal area observed during the 6-month follow-up period.

Several approaches are used for breast augmentation, including the widely practiced technique of placing an implant in the breast [9]. Despite the popularity and reliability of implantation, surgeons are exploring less invasive and simpler alternatives for breast augmentation, including the injection of fillers. Aquafilling is a copolyamide filler designed for breast augmentation. According to the manufacturerŌĆÖs instructions, Aquafilling is a hydrophilic gel that consists of 98% saline and 2% copolyamide.

The use of this filler for breast augmentation has not been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration [10] and is also prohibited in Korea [2]. Despite these restrictions, it has been administered in Korea as an off-label injection for breast enhancement.

Various complications associated with the use of copolyamide fillers have been increasingly reported across numerous countries. These complications include induration, masses, pain, firmness, contour irregularities, migration, and mastitis [4-8]. Notably, such issues do not typically present in the early stages following injection but often emerge later, complicating their management. A comprehensive radiologic evaluation is crucial for addressing these complications, with MRI being the most sensitive diagnostic tool. Aquafilling, like polyacrylamide gels, displays a water signal on MRI sequences, while it demonstrates hypointensity on T1-weighted sequences and hyperintensity on T2-weighted sequences. Additionally, it shows hyperintensity and diffusion restriction on diffusion-weighted imaging [1].

Breast cancer represents a major public health concern, as it is responsible for the highest numbers of incident cases and cancer-related deaths among women [11], as well as the greatest number of cancer-related disability-adjusted life-years [12]. Early screening is essential for reducing mortality from breast cancer [13]. In Korea, the National Cancer Screening Program mandates biennial mammography for women over 40 years old. Given that some women who have undergone breast augmentation with copolyamide filler have reached their 40s and are thus eligible for mammography, it is crucial to consider the risks associated with filler migration during the procedure, as illustrated by this case, even though such events are uncommon. While further ultrasonography may be performed if needed, studies have shown that copolyamide filler that has migrated into the surrounding fibroglandular tissue can form nodules, which may hinder the detection of breast cancer through ultrasonography. Consequently, breast ultrasonography alone may be insufficient for screening in women with a history of copolyamide filler use, and its utility is limited [5,7,14]. Although breast MRI can be a valuable supplementary tool, the costs involved may substantially limit its widespread use.

While the literature includes documented instances of distant migration and lymphadenopathy associated with silicone [15], no reports have been published concerning the distant migration of Aquafilling, particularly after mammography. Therefore, the present case is noteworthy. Our experience underscores the risks associated with the migration of copolyamide breast filler, especially in relation to cancer screening techniques. Clinicians and patients must be cognizant of these dangers and take them into account when selecting a cancer screening method. It is imperative to educate patients and obtain informed consent about the risks and complications associated with the migration of copolyamide breast filler during mammography. Additionally, regular monitoring and assessment are crucial.

Notes

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Soonchunhyang University Hospital (IRB No. 2023-05-009).

Patient consent

The patient provided written informed consent for the publication and use of her images.

Fig.┬Ā1.

A photograph of the patientŌĆÖs breasts shows asymmetry in size, with the right breast larger than the left. No other notable findings, such as subcutaneous nodules, granulomas, or fibrosis, were observed.

Fig.┬Ā2.

A photograph of the patientŌĆÖs abdomen shows an extensive oval-shaped fluid collection in the lower left quadrant. No other notable findings, such as subcutaneous nodules, granulomas, or fibrosis, were observed.

Fig.┬Ā3.

Breast magnetic resonance imaging reveals the presence of foreign body injection in both the prepectoral and subpectoral spaces, exhibiting high signal intensity on fat-suppressed T2-weighted images. No abnormal enhancing focal lesions were observed in the parenchyma of either breast.

REFERENCES

1. Ozcan UA, Ulus S, Kucukcelebi A. Breast augmentation with Aquafilling: complications and radiologic features of two cases. Eur J Plast Surg 2019;42:405-8.

2. Roh TS. Letter: position statement of Korean academic society of aesthetic and reconstructive breast surgery: concerning the use of aquafilling® for breast augmentation. Arch Aesthetic Plast Surg 2016;22:45-6.

3. Shin JH, Suh JS, Yang SG. Correcting shape and size using temporary filler after breast augmentation with silicone implants. Arch Aesthetic Plast Surg 2015;21:124-6.

4. Chalcarz M, Zurawski J. Injection of aquafilling® for breast augmentation causes inflammatory responses independent of visible symptoms. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2021;45:481-90.

5. Jung BK, Yun IS, Kim YS, et al. Complication of AQUAfilling® gel Injection for breast augmentation: case report of one case and review of literature. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2018;42:1252-6.

6. Loesch J, Eniste YS, Dedes KJ, et al. Complication after aquafilling® gel-mediated augmentation mammoplasty-galactocele formation in a lactating woman: a case report and review of literature. Eur J Plast Surg 2022;45:515-20.

7. Namgoong S, Kim HK, Hwang Y, et al. Clinical experience with treatment of Aquafilling filler-associated complications: a retrospective study of 146 cases. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2020;44:1997-2007.

8. Choi WJ, Song WJ, Kang SG. Complications and management of breast augmentation using two different types of fillers: a case series. Arch Aesthetic Plast Surg 2023;29:41-5.

9. American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Plastic surgery statistics report [Internet]. American Society of Plastic Surgeons; c2020 [cited 2023 May 16]. Available from: https://www.plasticsurgery.org/news/plastic-surgery-statistics

10. U.S. Food and Drug. Administration dermal fillers (soft tissue fillers) [Internet]. US Food and Drug Administration; c2023 [cited 2023 May 16]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/aesthetic-cosmetic-devices/dermal-fillers-soft-tissue-fillers

11. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:394-424.

12. Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration; Fitzmaurice C, Abate D, et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 29 cancer groups, 1990 to 2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol 2019;5:1749-68.

13. Choi E, Jun JK, Suh M, et al. Effectiveness of the Korean National Cancer Screening Program in reducing breast cancer mortality. NPJ Breast Cancer 2021;7:83.

-

METRICS

-

- 0 Crossref

- 694 View

- 114 Download

- Related articles in AAPS

-

Serratia marcescens infection in a patient after a fat graft: a case report2022 July;28(3)

Remote migration of breast filler to the inguinal area: a case report2021 October;27(4)